STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Coca-Cola -- the world's ubiquitous brown fizzy drink -- is staying afloat as the soda market shrinks

- Many point to a marketing strategy around the so-called "secret recipe" as key to its resilience

- It's never been patented, to keep the formula secret, but many say they have discovered the recipe

The Coca-Cola Company,

which published its full year result Tuesday, recorded a 5% drop in net

income to $8.6 billion last year, down from $9 billion in 2012, as it

faced "ongoing global macroeconomic challenges," according to its chief

executive Muhtar Kent.

Volume grew 2% for the

year, which it said was "below our expectations and long-term growth

target," with sparkling beverages recording a slight increase of 1% --

led by Coca-Cola.

Globally, soda drink

sales have been shrinking as consumers turn to water, fruit drinks and

healthier alternatives. The trend has hit Coke and other market players

such as PepsiCo and Dr. Pepper. And while its primary competitor,

PepsiCo, depends on its snack business to buoy the declining soda sales,

Coke announced further investment into its marketing.

Coke in a K-Cup?

Coke in a K-Cup?

The business of the World Cup

The business of the World Cup

In a tough market, one

strategy that brand experts credit Coke's relative strength with is the

mystery around the much-hyped "secret recipe."

"The very idea of mystery

attracts attention, and is often seen as an element of quality," says

social psychologist and marketing expert Ben Voyer, lecturer at London

School of Economics and ESCP Europe Business School. "A typical consumer

would think that it must be a valuable product if they are doing all

these things to protect the recipe."

Coca-Cola's "secret

recipe" story -- on which it has centered advertising campaigns and

built into its corporate museum --- reaches back nearly a century.

According to the multi-national's website, the original recipe was only

written down in 1919, more than half a century after a reported morphine

addict and pharmacist John Pemberton invented the drink in 1866. Until

then, it was passed down by word of mouth.

The formula was finally

committed to paper when a group of investors led by Ernest Woodruff took

out a loan to purchase the company in 1919. "As collateral, he provided

a written record of the Coca Cola secret formula," Coke said in a

statement on its site.

Since the 1920s, the

document sat locked in a bank in Atlanta, until Coca-Cola decided to

emphasize the secret in its marketing strategy. 86 years later,

Coca-Cola moved the recipe into a purpose-built vault within the World

of Coca-Cola, the company's museum in Atlanta. The ambiance is made

complete by red lighting and fake smoke.

Coca-Cola has always

claimed only two senior executives know the formula at any given time,

although they have never revealed names or positions. But according to

an advertising campaign based around the recipe, they can't travel on

the same plane.

The vault, like one straight from a film, has a palm scanner, a numerical code pad and massive steel door.

Mark Pendergrast, author of For God, Country and Coca-Cola, says this is the real deal.

Inside its walls,

there's another safe box with more security features. And inside that, a

metal case containing what its owners call "the most guarded trade

secret in the world." A piece of paper with, according to Coca-Cola, a

recipe inside.

But Mark Pendergrast,

author of For God, Country and Coca-Cola, is skeptical. "They kept the

formulas secret, partly in order to increase sales with a sense of

special mystery and to prevent competition, but also to keep people from

knowing how cheap the ingredients were and how large the profits," he

says.

The company has never

patented the formula, saying to do so would require its disclosure. And

once the patent expired, anyone would be able to use that recipe to

produce a generic version of the world famous drink.

"[The secrecy] creates a

natural curiosity about the product itself. Consumers are more likely

to try to find out the recipe," Voyer says, adding it creates a legend

around Coca Cola's flagship drink.

The business behind the World Cup

The business behind the World Cup

Coke's new ad campaign: It's safe

Coke's new ad campaign: It's safe

Scores of recipes have

emerged through the decades. Their authors usually claim to have cracked

the original recipe by getting hold of antique documents. So far, Coke

has rejected all of them as fantasy, saying there is only one "'real

thing'."

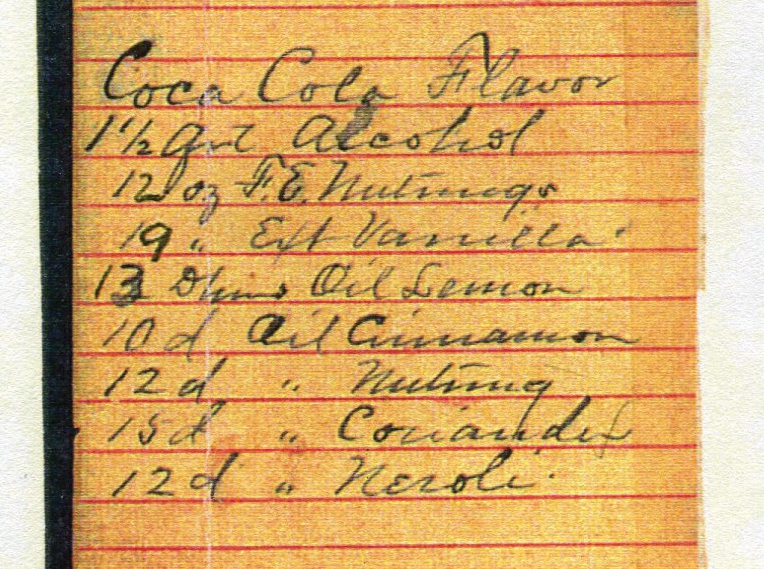

Mark Pendergrast's book

includes two versions of the original formula. "One is a facsimile in

the handwriting of Frank Robinson, the "unsung hero" of Coca-Cola who

named the drink, wrote the famous script logo, manufactured the drink in

its early days, and advertised it," he says.

Does he think the recipe is genuine?

"Yes. I think that both

of the Coca-Cola formulas in my book are the "real thing," versions of

the original formula for Coca-Cola," he says.

"In the end, the exact

formula isn't really the issue," he says. Pendergrast reiterates a tale

told in his book, in which he speaks to a Coca-Cola spokesperson who

points out that even if its competitors got hold of the formula, they

wouldn't be able to compete. "Why would anyone go out of their way to

buy Yum-Yum, which is really just like Coca-Cola but costs more, when

they can buy the Real Thing anywhere in the world?," he was told

Coca-Cola claims its formula is

the "world's most guarded secret." The recipe, the company says, is now

kept in a purpose-built vault within the company's headquarters in

Atlanta.

Coca-Cola claims its formula is

the "world's most guarded secret." The recipe, the company says, is now

kept in a purpose-built vault within the company's headquarters in

Atlanta.

No comments:

Post a Comment